Erin Meyer’s The Culture Map details how each individual is conditioned by their own culture. If we were fish in the sea, culture would be the water: invisible, yet part of our everyday lives.

Meyer illustrates this conditioning through specific behavioral scales. For instance, while low-context cultures focus on the directness of information, high-context cultures rely on “reading between the lines.” (As an example, the U.S. is the lowest-context culture in the world, while Japan is the highest). She uses a total of eight such principles to precisely describe each culture within a work environment lens.

Now, what if we applied this same approach to the way we taste things?

The intricate dance of flavor perception, culinary preference, and dining etiquette is not governed by a universal biological standard. Instead, like business interactions, it is profoundly shaped by these invisible currents of culture. This document will demonstrate that the experience of flavor is not a biological absolute but a cultural language. By decoding this language using Meyer’s framework, we will reveal how different societies perceive, structure, and critique the act of eating, moving from simple observation to sophisticated, culturally intelligent engagement with the global palate.

Before applying the cultural map to the complexities of taste, it is essential to understand both the framework itself and the scientific basis for why taste is a valid and vital subject for cultural analysis. This section lays the groundwork by defining Meyer’s eight dimensions and establishing that our sensory perception of flavor is not uniform, but is biologically and geographically diverse, creating a rich canvas upon which culture paints its preferences.

Erin Meyer’s eight-dimensional framework is a tool designed to map cultural differences in professional settings, helping global teams decode one another’s behavior and improve effectiveness. It plots national cultures along a spectrum for each of the following eight scales:

Communicating: low-context vs. high-context

Evaluating: direct negative feedback vs. indirect negative feedback

Persuading: principles-first vs. applications-first

Leading: egalitarian vs. hierarchical

Deciding: consensual vs. top-down

Trusting: task-based vs. relationship-based

Disagreeing: confrontational vs. avoids confrontation

Scheduling: linear-time vs. flexible-time

The perception of taste is not uniform across all human populations. Far from being a universal constant, our sensory experience is heavily influenced by inherited biological factors that create a baseline for how we perceive core flavors.

The primary mechanism for this variation is genetic. Individual DNA determines the number of taste receptors on the tongue that detect sweet, sour, salty, bitter, and umami compounds. This genetic lottery results in significant differences in taste sensitivity between individuals and, more broadly, between entire populations.

One of the most striking examples is the Geographical Bitter Tolerance Disparity. Research shows that sensitivity to specific bitter compounds “varies wildly between different countries.” Populations native to parts of Asia, South America, and Africa exhibit remarkably high sensitivity, with up to 85% of individuals classified as highly sensitive tasters. In contrast, populations of ethnic European descent are generally at the lower end of this sensitivity scale. These inherent biological and geographical variations provide a firm scientific foundation for exploring how cultural conditioning further shapes the experience, evaluation, and celebration of flavor.

The menu is a legal code, the dining table a courtroom, and the chef a political leader. To understand the global palate is to understand that every meal is governed by a set of invisible cultural laws. Here, we decode those laws using Meyer’s eight statutes of human interaction, reinterpreting each dimension through the lens of culinary practices, consumer behavior, and the sensory experience of flavor. This analysis will reveal how deeply culture dictates our relationship with food, from how we talk about it to how we share it.

The Communicating scale contrasts cultures that favor Low-Context communication (precise, simple, clear) with those that rely on High-Context communication (nuanced, layered, implicit). This dimension manifests as a fundamental split in the culinary story. In low-context cultures like the U.S., the narrative is etched onto the packaging, a quantitative tale of ingredients, nutritional data, and explicit flavor profiles. The product’s value is proven by its objective attributes. Conversely, in high-context Japan, the story is found not on the box but in the theater of the experience: the silent ballet of the service, the visual harmony of the plating, and the unspoken history of the dish. Here, value is implicit and derived from context.

The Evaluating scale contrasts cultures that deliver negative feedback directly (frank, blunt) with those that prefer an indirect approach (soft, subtle, diplomatic). This dimension governs how consumers and critics express satisfaction or dissatisfaction with food.

This cultural variance creates a significant challenge in global sensory science, known as the “Response Compression Dilemma.” When asked to rate products on a numerical scale, participants from different cultures use the scale in predictably different ways, a moment where researchers are, in effect, forcing the fish to describe the water using a foreign vocabulary. A comparative study of taste ratings found that while Thai participants (an Indirect culture) consistently used a smaller portion of the rating scales and avoided the extremes, Dutch participants (a Direct culture) used the full range of the scale freely to express strong approval or disapproval.

This “scale compression” is not a reflection of lesser enjoyment; it is a cultural mandate against the social transgression of expressing extreme, blunt opinions. An 8 out of 10 in an Indirect market may represent the same level of satisfaction as a 10 out of 10 in a Direct one.

The Persuading scale contrasts cultures that favor Principles-first reasoning (deductive, moving from a general theory to a practical conclusion) with those that prefer Applications-first reasoning (inductive, drawing general conclusions from real-world observations). This logic dictates both how novel foods gain acceptance and how traditional flavors are combined.

This dimension profoundly impacts how consumers approach radical food innovations like cultured meat. Principles-first markets (e.g., many in Europe) require theoretical validation before they will consider the application. Consumers in these markets are persuaded by the why. For an innovation to be accepted, it must first be proven safe, ethical, and philosophically sound through comprehensive data and regulatory endorsement. In contrast, Applications-first markets (e.g., the United States) are persuaded by the how. Innovation succeeds if it demonstrates immediate, practical superiority. A new product will gain traction if it tastes better, is more convenient, or provides greater value than existing options, with less initial emphasis on the underlying theory.

This same persuasive logic is embedded in the very structure of traditional cuisines. Traditional European gastronomy, reflecting Applications-first thinking, often favors combining ingredients that share flavor compounds. This logic is inductive, derived from centuries of observing which pairings work in practice. This applications-first logic, built on observing successful pairings, may have been biologically reinforced; in cultures with a lower genetic sensitivity to bitterness (e.g., ethnic Europeans), the celebration of bitter flavor compounds found in aperitifs, dark greens, and coffee became a mark of culinary sophistication, rather than a taste to be masked. Conversely, traditional Asian cuisines systematically avoid combining ingredients with similar flavors. This approach reflects a Principles-first logic, adhering to foundational theoretical principles of balance, harmony, and complementarity.

The Leading scale measures the ideal distance between a leader and a subordinate. In Egalitarian cultures, this distance is small. In Hierarchical cultures, it is large. This directly translates to the power dynamics and protocols of a shared meal.

In Hierarchical cultures (e.g., China, India), the boss, host, or senior figure is a clear authority who may order for the entire group. Strict rules of etiquette and deference are observed to show respect for their position. In contrast, in Egalitarian cultures (e.g., Denmark, Netherlands), power distinctions are intentionally blurred. Input on meal selection is often inclusive, and formal etiquette is less critical than demonstrating equality. A Dutch host inviting a plumber for a cup of tea is a classic example of this principle, an indication that individuals are viewed as equals regardless of the work they do.

The Deciding scale contrasts cultures that value group agreement (Consensual) with those where an individual, typically the leader, makes decisions for the group (Top-down). This dimension governs everything from professional menu development to ordering at a group dinner.

Top-down food decisions are common in environments where a single authority figure holds sway. This can be seen in the traditional haute cuisine kitchen, where the executive chef’s vision is absolute, or in a hierarchical group dinner where the most senior person orders for the table. Consensual food decisions emphasize collective agreement. In Japanese group dining, for instance, significant time may be spent negotiating shared dishes to ensure everyone is accommodated and a harmonious group choice is reached.

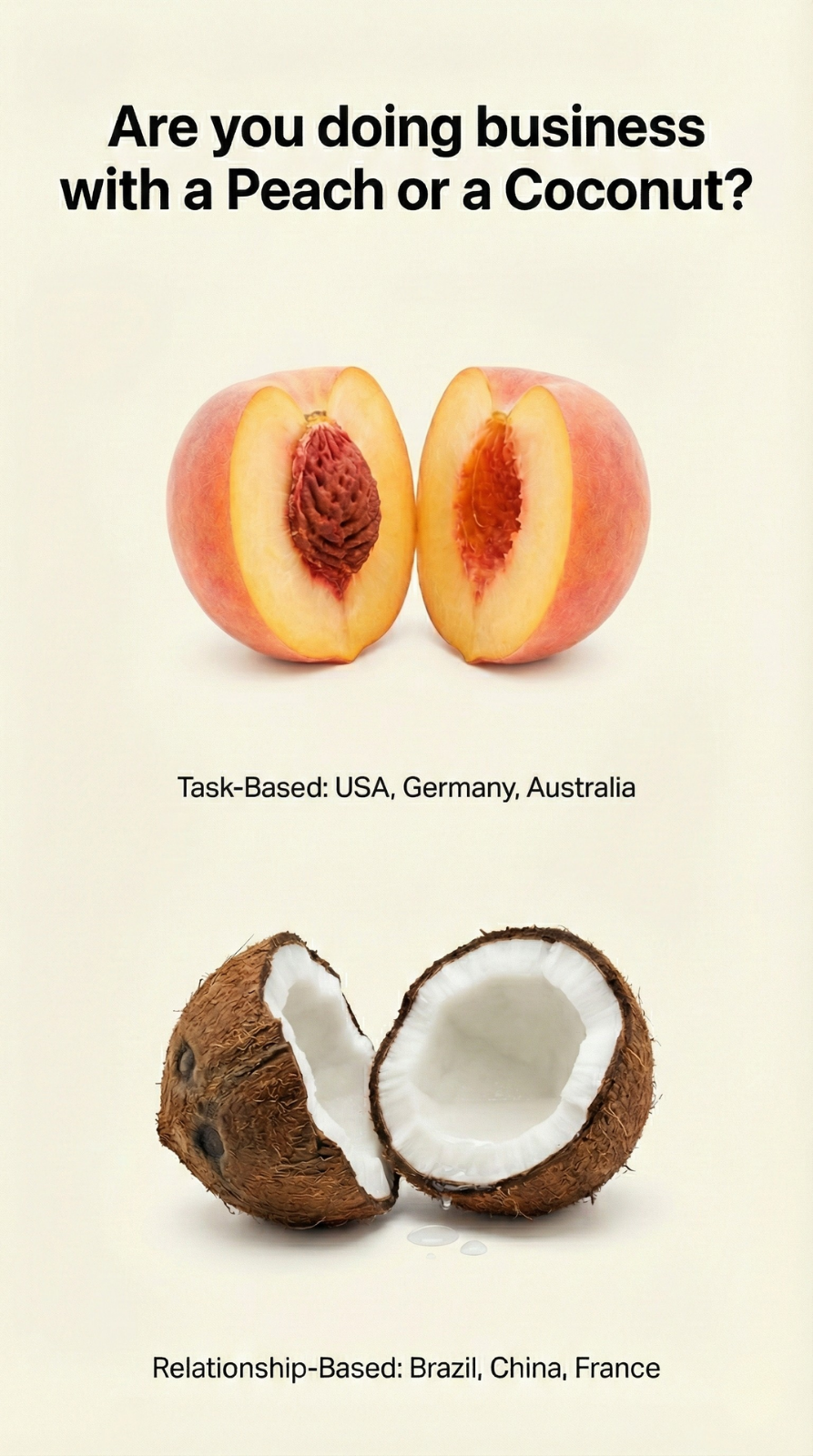

The Trusting scale distinguishes between two pathways to building confidence. In Task-based cultures, trust is primarily cognitive, built through demonstrated professional competence, it “comes from the head.” In Relationship-based cultures, trust is primarily affective, built through personal connection and shared experience, it “comes from the heart.” This profoundly alters the fundamental purpose of a business meal.

In Task-based cultures (e.g., the U.S., Germany), the meal is a transactional venue for efficiently exchanging information. Proper dining etiquette is a component of professionalism that ensures the meal proceeds without distraction. This dichotomy is brilliantly illustrated by the “peach” versus “coconut” model. Task-based ‘peach’ cultures like the U.S. are socially soft on the outside, encouraging easy small talk, but keep a hard pit of private life guarded.

In Relationship-based cultures (e.g., Brazil, China, Saudi Arabia), the meal is the primary vehicle for building the personal connection that underpins trust. Here, dining etiquette is not a social nicety but, as career development literature emphasizes, a critical competency that can “make or break a potential business relationship.” These ‘coconut’ cultures are hard on the exterior, making initial interactions formal. However, once that barrier is broken, the relationship is deep and encompassing, merging the personal and professional.

The Disagreeing scale measures a culture’s tolerance for open disagreement. In Confrontational cultures, debate is seen as positive, while in cultures that Avoid Confrontation, disagreement is viewed as a negative disruption to group harmony.

In Confrontational cultures (e.g., France, Israel), openly debating a dish’s merits or sending it back to the kitchen is considered acceptable and constructive. The focus is on resolving the issue directly. In cultures that Avoid Confrontation (e.g., Indonesia, Japan), maintaining social harmony and saving face for the chef or server is the priority. Negative feedback is either suppressed or delivered with extreme subtlety and indirectness to avoid causing offense.

At last, the Scheduling scale contrasts Linear-time cultures, where time is sequential and schedules are paramount, with Flexible-time cultures, where time is fluid and adaptable to changing social needs.

Linear-time dining (e.g., Germany, U.S.) is characterized by a focus on punctuality, adherence to reservation times, and an orderly progression of courses. The schedule dictates the meal, and delays are viewed as unprofessional disruptions. Flexible-time dining (e.g., Saudi Arabia, Brazil) is organized around social connection, not the clock. Start times are adaptable, interruptions are accepted as natural, and the meal’s duration is determined by the needs of the relationship, often extending indefinitely to foster rapport.

Taste is a cultural language, rich with implicit rules and deep-seated logic. Applying Erin Meyer’s eight-dimensional framework acts as a “Rosetta Stone,” allowing us to systematically decode this language and understand why one culture’s ambrosial delicacy is another’s acrid afront.

For any organization operating in the global food and beverage landscape, this perspective offers immense value. It enables more nuanced market entry strategies, more effective product development cycles, and more successful relationship management. By moving beyond surface-level preferences to understand the underlying cultural grammar of taste, businesses can gain a profound and sustainable competitive advantage in a complex and diverse world.