I was going for lunch in downtown Orlando, on a Saturday. As we entered the restaurant, a guy in a flannel shirt casually ordered kimchi taco.

No one explained what kimchi was. It wasn’t “exotic” or anything. It was just lunch.

That moment confirms something I’d been tracking for months: East Asian flavors are now a part of the American culinary landscape. Not just a trend, but a cultural shift.

The takeover is complete

Yuzu, miso, kimchi, and gochujang have broken out of their ethnic food etiquette. You’ll find them in gas station snacks and Walmart condiment aisles. Even your local diner probably has Sriracha mayo.

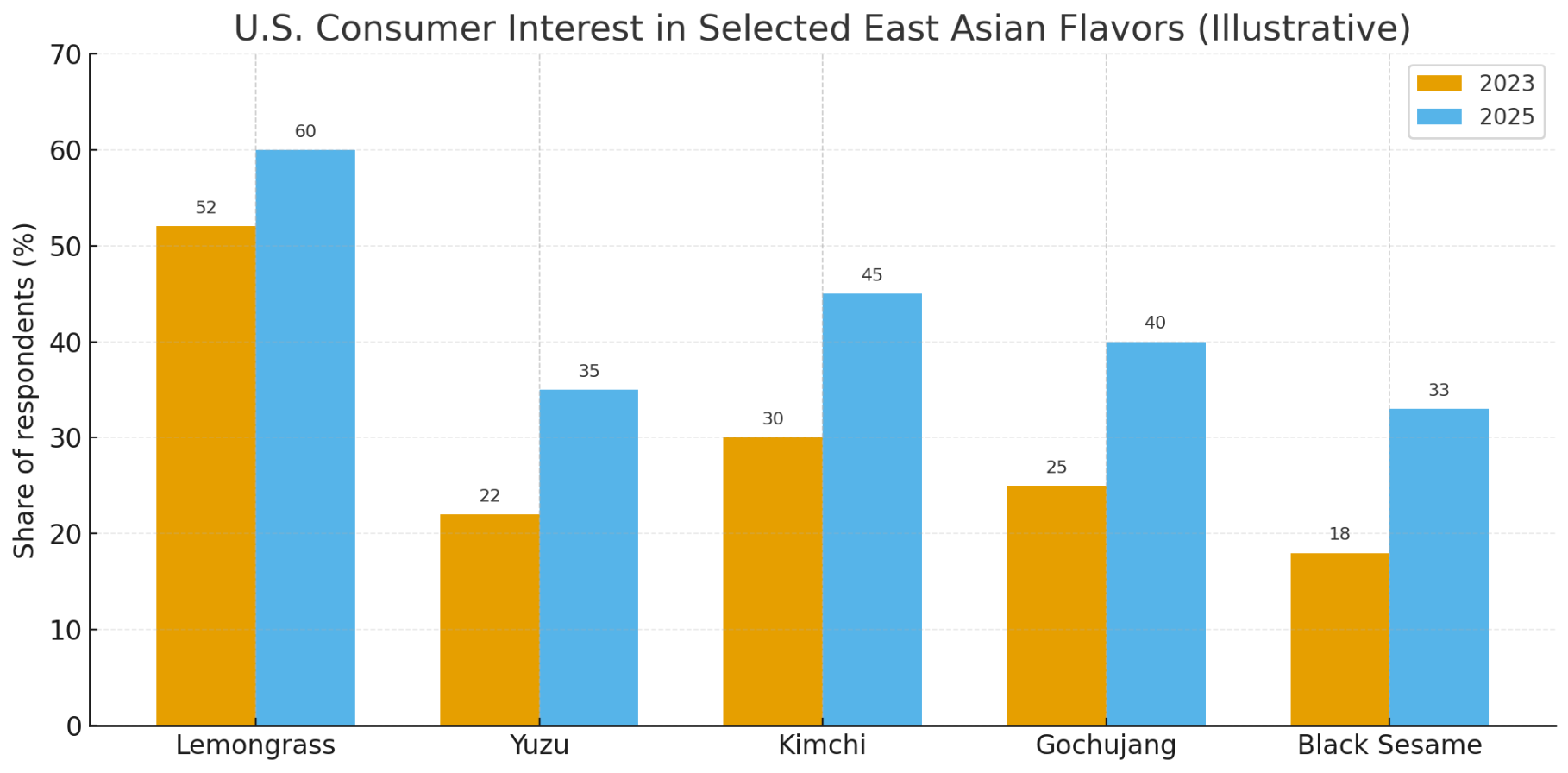

Consumers are hungry for it

Half of Americans actively look for global flavors. For lemongrass alone, 65% of US consumers report interest. Gen Z and Millennials are leading the demand, but they want the real thing, with authentic flavors.

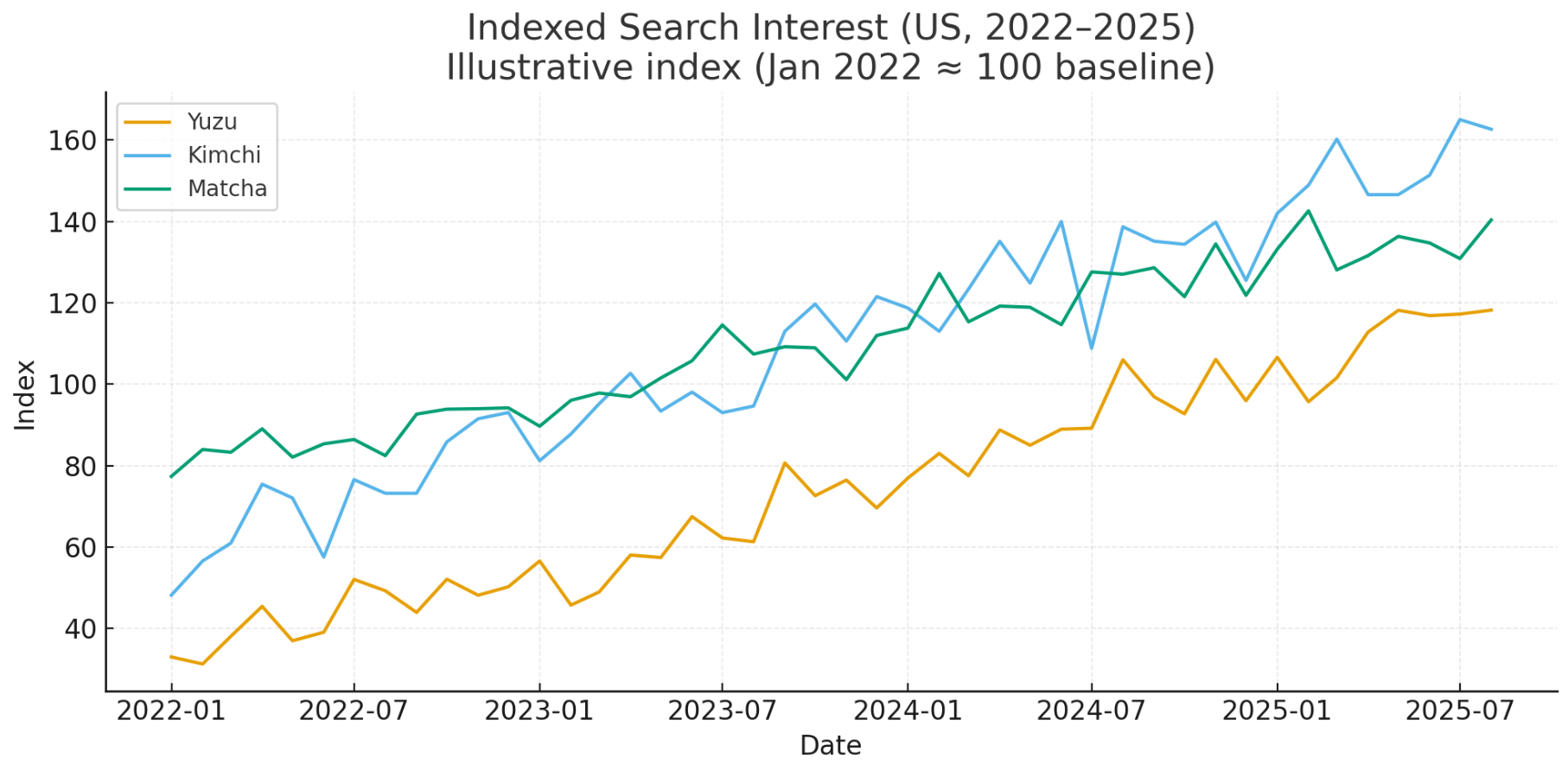

The numbers

Chinese, Japanese, Vietnamese, and Korean flavors drove one-third of all global ethnic product launches recently. US kimchi imports jumped 37% year-over-year in 2023. The global kimchi market hit $4.9 billion, with North America claiming 16% of that pie.

R&D reality

Formulating with these ingredients is like trying to tame a beautiful, volatile beast. Kimchi’s sour, miso’s sodium, yuzu’s expensive aromatics, they all demand respect and clever chemistry.

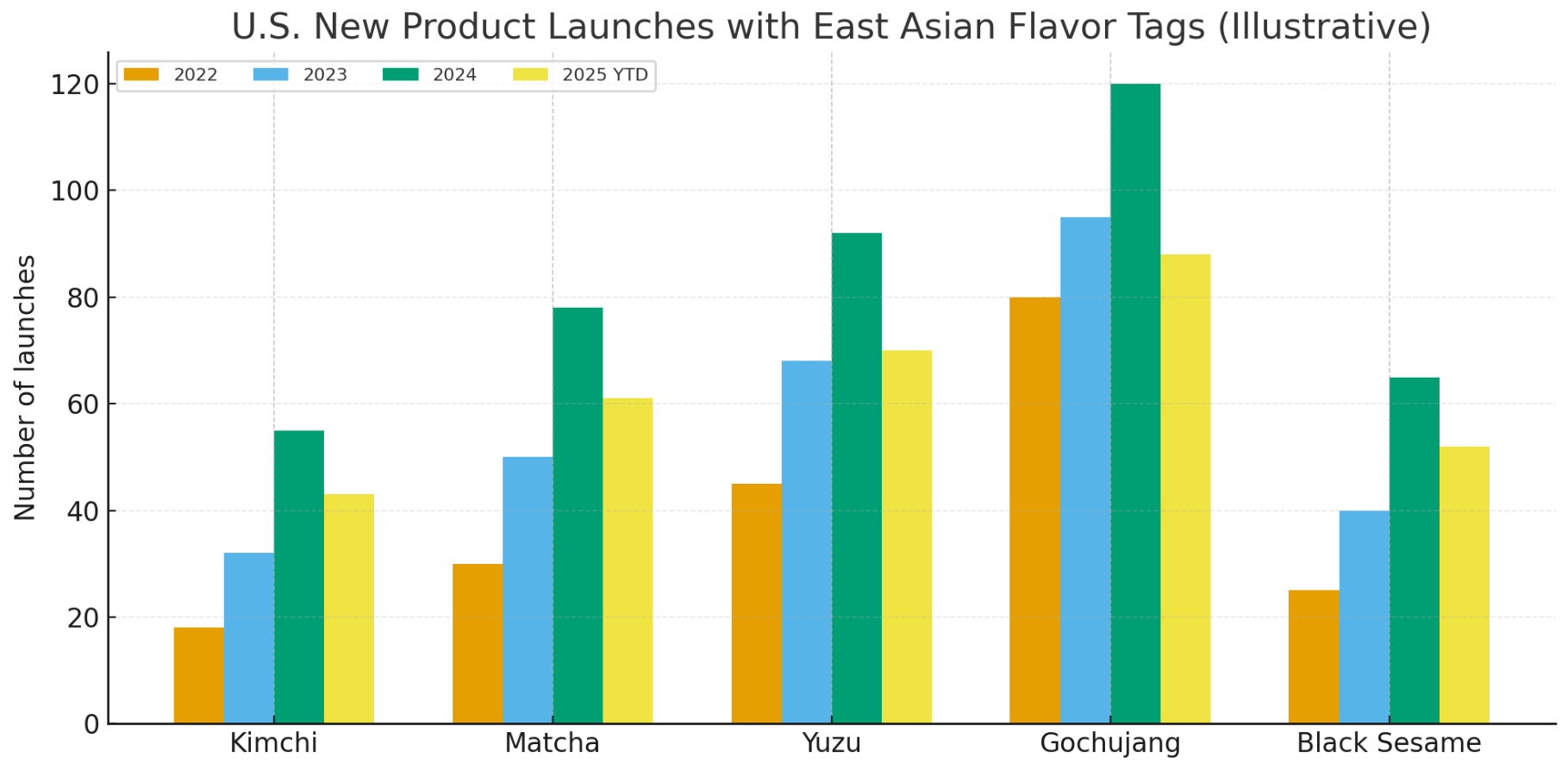

Big players are paying attention

CJ Bibigo’s kimchi sits on Walmart shelves. Givaudan is developing yuzu essences. The flavor houses with the most authentic flavor profiles will own the premium positioning.

The shift happened quietly, then all at once. First, the sushi boom normalized raw fish and wasabi. Then Korean BBQ made gochujang a staple of Asian cuisine abroad. Then social medias got hold of kimchi pancakes and matcha everything, and the floodgates opened.

Now Japanese restaurants abroad have grown 20% between 2021 and 2023, with the US leading. And South Korea’s kimchi exports hit a record 44,000+ tons in 2023.

Roughly half of Americans want stores to stock more of their favorite global flavors. But here’s what’s interesting: they’re not only curious about these tastes, they’re also getting sophisticated about them.

A young barista can now easily tell you the difference between ceremonial-grade matcha and a Dunkin’ one (sorry Dunkin). Millennials fonds of California rolls can now spot authentic fermented kimchi versus the mass-produced.

Social media accelerated everything. What started as exotic quickly became expected.

Walk any supermarket aisle and you’ll see the conquest in action. Japanese sodas flavored with yuzu and umeboshi sit next to Coca-Cola. Korean seaweed chips compete with Lay’s. Miso butter appears in the dairy case like it’s been there forever.

Even the comfort food categories is being impacted. Mac and cheese with miso. Barbecue sauce and gochujang. Even vanilla ice cream made room for black sesame and ube… This is only the start of it.

Here’s where it gets interesting for those of us in product development. East Asian taste profiles are complex on a whole other level.

Take yuzu for example. It’s citrus, but not like any lemon or lime. Those herbal top notes and floral aldehydes create a completely different sensory experience.

Black sesame brings nutty sweetness with an edge of bitterness that can either complement or fight other flavors, depending on how you handle it.

Fermented ingredients like miso and gochujang carry an umami depth that can overwhelm if you’re not careful. They’re salty, funky, and loaded with compounds that interact unpredictably with other ingredients. Matcha’s vegetal astringency can turn beautifully earthy or unpleasantly grassy based on processing and application.

This is where the rubber meets the road, and where most companies fail.

Kimchi looks simple until you try to put it in a cookie. All the tangy, spicy water doesn’t work with shelf-stable formats. Miso’s sodium content and MSG-like compounds can overwhelm delicate applications. Yuzu oil costs more per ounce than decent whiskey and can evaporates quickly.

Then there are the allergen. Soy and sesame are everywhere in authentic Asian ingredients. Clean-label claims get complicated when you’re dealing with fermented products that require specific preservation strategies.

The volatiles are particularly brutal. Yuzu’s signature aroma compounds are as delicate as they are expensive. Many brands resort to blending with cheaper citrus oils or microencapsulation, which can work, but often loses that ethereal complexity that makes yuzu worth using in the first place.

Traditional processing methods don’t always translate to industrial scale. Fermenting kimchi in-house demands time, space, and specialized knowledge. Most companies end up using extract powders that capture some essence but miss the nuanced funk of the real thing.

Big condiment brands rolled out Asian-inspired lines. Sriracha ketchup, wasabi mustard, the list goes on… Korean conglomerates invested in US facilities: Daesang’s new kimchi plant, Pulmuone’s adapted tofu lines, all to answer to a surging demand.

Flavor houses face their own battles. Givaudan and Firmenich rush to patent proprietary profiles while startups capture niche edges with “real fermented chili crunch” or pre-aged tofu marinades. The dominant innovation hubs cluster in New York, San Francisco, and Chicago, but regional labs pop up wherever ethnic food communities create demand.

Early movers who authentically master these profiles, with Kikkoman’s gaining a premium positioning.

The fun part? We’re just getting started. East Asian flavors graft beautifully onto proven American formats: kimchi Philly cheesesteaks, yuzu-lime potato chips, matcha peanut butter cookies. Health angles provide additional hooks such as ginger turmeric teas, seaweed-fortified broths…

Watch the micro-trends: pandan and ube from Philippine, yuzu pepper condiments, Vietnamese curry sauces. Brands integrating multiple ethnic notes stand out on increasingly crowded menus.

For global brands eyeing the US market, localization remains key. Reduce heat for Midwestern palates, accentuate smoky-sweet notes for the South…

These profiles require understanding, not just of their sensory properties, but of their cultural context and authentic preparation methods. The difference between real fermented kimchi and “kimchi-flavored” anything is the difference between a considered dish and a gimmick.

The formulation challenges are real nonetheless: managing salt levels in miso applications, stabilizing volatile aromatics in yuzu products, balancing heat and tang in gochujang formulations. Equipment considerations matter too. Fermenting in-house versus using extracts, handling allergens, meeting clean-label expectations.

But here’s the thing about difficult ingredients: they reward the companies willing to do the work. The technical barriers that make these flavors challenging to formulate also make them hard to replicate cheaply. Master the profiles, and you own premium positioning in categories where consumers happily pay more for authenticity.

The East Asian cuisine is a fundamental shift in American food culture, led by demographic change, social media amplification, and genuine consumer sophistication. The mainstreaming of those flavors represents the largest flavor category expansion I’ve witnessed so far.

Food and beverage developers who authentically capture these profiles, yuzu kombucha, black sesame ice cream, ginger miso protein bars… are already getting ahead in the race for innovation. The technical challenges are significant, but so is the opportunity.

Thanks for reading